Git 101: Git and GitHub for beginners.

By Meghan Nelson (Software Engineer, HubSpot)

Last summer, we hosted a Women Who Code Meetup at HubSpot and led a workshop for beginners on using git and GitHub. I first walked through a slide presentation on the basics and background of git and then we broke out into groups to run through a tutorial I created to simulate working on a large, collaborative project. We got feedback after the event that it was a helpful, hands-on introduction. So if you’re new to git, too, follow the steps below to get comfortable making changes to the code base, opening up a pull request (PR), and merging code into the master branch. Any important git and GitHub terms are in bold with links to the official git reference materials.

Step 0: Install Git and Create a GitHub Account

The first two things you’ll want to do are install git and create a free GitHub account.

Follow the instructions to install git (if it’s not already installed). Note that for this tutorial we will be using git on the command line only. While there are some great git GUIs (graphical user interfaces), I think it’s easier to learn git using git-specific commands first and then to try out a git GUI once you’re more comfortable with the command.

Once you’ve done that, create a GitHub account. (Accounts are free for public repositories, but there’s a charge for private repositories.)

Step 1: Create a Local Git Repository

When creating a new project on your local machine using git, you’ll first create a new repository (or often, ‘repo’, for short).

To use git we’ll be using the terminal. If you don’t have much experience with the terminal and basic commands, check out this tutorial (especially the ‘Navigating the Filesystem’ and ‘Moving Around’ sections).

To begin, open up a terminal and move to where you want to place the project on your local machine using the cd (change directory) command. For example, if you have a ‘projects’ folder on your desktop, you’d do something like:

To initialize a git repository in the root of the folder, run the git init command:

Step 2: Add a New File to the Repo

Go ahead and add a new file to the project, using any text editor you like or running a touch command.

Once you’ve added or modified files in a folder containing a git repo, git will notice that changes have been made inside the repo. But, git won’t officially keep track of the file (that is, put it in a commit – we’ll talk more about commits next) unless you explicitly tell it to.

After creating the new file, you can use the git status command to see which files git knows exist.

What this basically says is, “Hey, we noticed you created a new file called mnelson.txt, but unless you use the ‘git add’ command we aren’t going to do anything with it.”

An Interlude: The Staging Environment, the Commit, and You

One of the most confusing parts when you’re first learning git is the concept of the staging environment and how it relates to a commit.

A commit is a record of what files you have changed since the last time you made a commit. Essentially, you make changes to your repo (for example, adding a file or modifying one) and then tell git to put those files into a commit.

Commits make up the essence of your project and allow you to go back to the state of a project at any point.

So, how do you tell git which files to put into a commit? This is where the staging environment or index come in. As seen in Step 2, when you make changes to your repo, git notices that a file has changed but won’t do anything with it (like adding it in a commit).

To add a file to a commit, you first need to add it to the staging environment. To do this, you can use the git add <file name> command (see Step 3 below).

Once you’ve used the git add command to add all the files you want to the staging environment, you can then tell git to package them into a commit using the git commit command.

Note: The staging environment, also called ‘staging’, is the new preferred term for this, but you can also see it referred to as the ‘index’.

Step 3: Add a File to the Staging Environment

Add a file to the staging environment using the git add command.

If you rerun the git status command, you’ll see that git has added the file to the staging environment (notice the “Changes to be committed” line).

To reiterate, the file has not yet been added to a commit, but it’s about to be.

Step 4: Create a Commit

It’s time to create your first commit! Run the command git commit -m “Your message about the commit”

The message at the end of the commit should be something related to what the commit contains – maybe it’s a new feature, maybe it’s a bug fix, maybe it’s just fixing a typo. Don’t put a message like “asdfadsf” or “foobar”. That makes the other people who see your commit sad. Very, very, sad.

Step 5: Create a New Branch

Now that you’ve made a new commit, let’s try something a little more advanced.

Say you want to make a new feature but are worried about making changes to the main project while developing the feature. This is where git branches come in.

Branches allow you to move back and forth between ‘states’ of a project. For instance, if you want to add a new page to your website you can create a new branch just for that page without affecting the main part of the project. Once you’re done with the page, you can merge your changes from your branch into the master branch. When you create a new branch, Git keeps track of which commit your branch ‘branched’ off of, so it knows the history behind all the files.

Let’s say you are on the master branch and want to create a new branch to develop your web page. Here’s what you’ll do: Run git checkout -b <my branch name>. This command will automatically create a new branch and then ‘check you out’ on it, meaning git will move you to that branch, off of the master branch.

After running the above command, you can use the git branch command to confirm that your branch was created:

The branch name with the asterisk next to it indicates which branch you’re pointed to at that given time. Now, if you switch back to the master branch and make some more commits, your new branch won’t see any of those changes until you merge those changes onto your new branch.

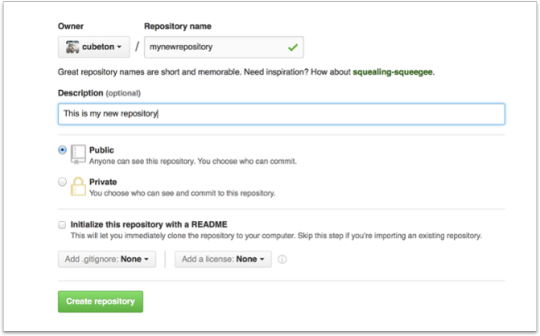

Step 6: Create a New Repository on GitHub

If you only want to keep track of your code locally, you don’t need to use GitHub. But if you want to work with a team, you can use GitHub to collaboratively modify the project’s code. To create a new repo on GitHub, log in and go to the GitHub home page. You should see a green ‘+ New repository’ button:

(You’ll want to change the URL in the first command line to what GitHub lists in this section since your GitHub username and repo name are different.)

Step 7: Push a Branch to GitHub

Now we’ll push the commit in your branch to your new GitHub repo. This allows other people to see the changes you’ve made. If they’re approved by the repository’s owner, the changes can then be merged into the master branch.

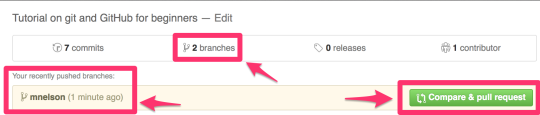

To push changes onto a new branch on GitHub, you’ll want to run git push origin yourbranchname. GitHub will automatically create the branch for you on the remote repository:

You might be wondering what that “origin” word means in the command above. What happens is that when you clone a remote repository to your local machine, git creates an alias for you. In nearly all cases this alias is called “origin.” It’s essentially shorthand for the remote repository’s URL. So, to push your changes to the remote repository, you could’ve used either the command: git push git@github.com:git/git.git yourbranchname or git push origin yourbranchname (If this is your first time using GitHub locally, it might prompt you to log in with your GitHub username and password.) If you refresh the GitHub page, you’ll see note saying a branch with your name has just been pushed into the repository. You can also click the ‘branches’ link to see your branch listed there.

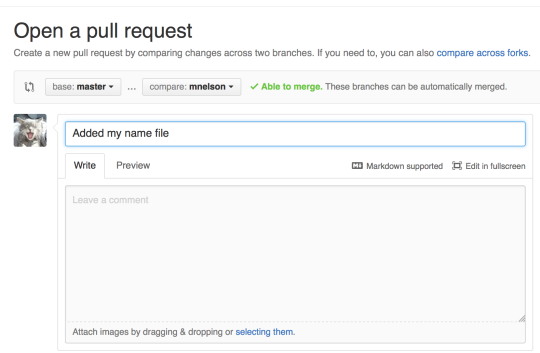

Step 8: Create a Pull Request (PR)

A pull request (or PR) is a way to alert a repo’s owners that you want to make some changes to their code. It allows them to review the code and make sure it looks good before putting your changes on the master branch. This is what the PR page looks like before you’ve submitted it:

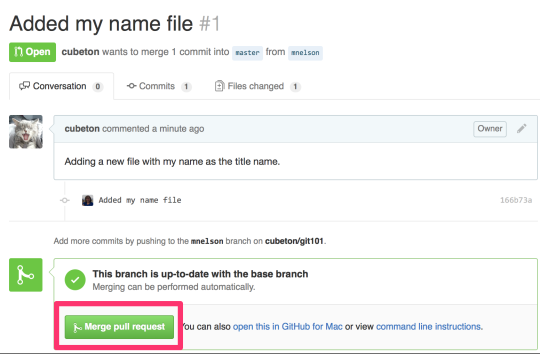

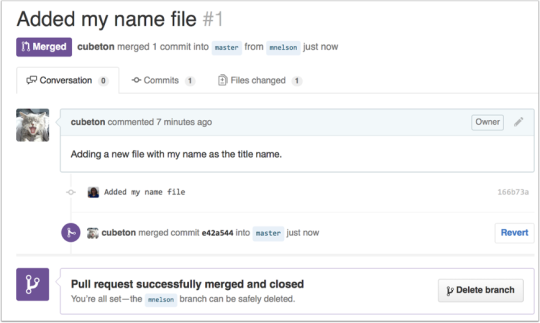

Step 9: Merge a PR

Go ahead and click the green ‘Merge pull request’ button. This will merge your changes into the master branch.

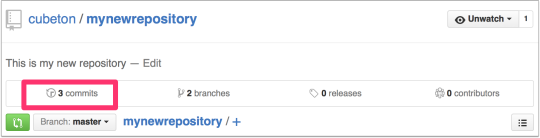

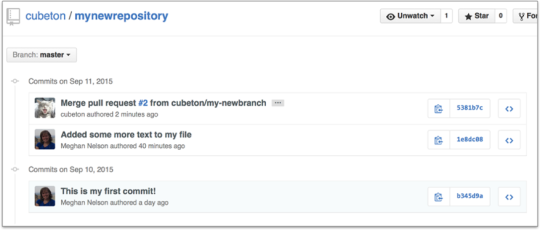

Step 10: Get Changes on GitHub Back to Your Computer

Right now, the repo on GitHub looks a little different than what you have on your local machine. For example, the commit you made in your branch and merged into the master branch doesn’t exist in the master branch on your local machine. In order to get the most recent changes that you or others have merged on GitHub, use the git pull origin master command (when working on the master branch).

This shows you all the files that have changed and how they’ve changed.

Now we can use the git log command again to see all new commits.

(You may need to switch branches back to the master branch. You can do that using the git checkout master command.)

Step 11: Bask in Your Git Glory

You’ve successfully made a PR and merged your code to the master branch. Congratulations! If you’d like to dive a little deeper, check out the files in this Git101 folder for even more tips and tricks on using git and GitHub.

I also recommend finding some time to work with your team on simulating a smaller group project like we did here. Have your team make a new folder with your team name, and add some files with text to it. Then, try pushing those changes to this remote repo. That way, your team can start making changes to files they didn’t originally create and practice using the PR feature. And, use the git blame and git history tools on GitHub to get familiar with tracking which changes have been made in a file and who made those changes.

The more you use git, the more comfortable you’ll… git with it. (I couldn’t resist.)

About the guest blogger: Meghan Nelson is a software engineer at HubSpot. Follow the HubSpot product team on Twitter at @HubSpotDev.