Women are making progress despite the system, and they need our help.

Women are still very much a minority in Silicon Valley. Fewer than 30% of tech workers are women, fewer than 20% board members, 17% startup founders and 8% investment partners. Many women feel that the system is rigged against them. It feels rigged when you were the only woman in your computer science class, get a job as an engineer in a highly competitive company, and are told that women aren’t suited to engineering. It feels rigged when Juicero raises millions of dollars in funding for pointless tech, and your breakthrough product doesn’t get funded because VCs think it’s a “women’s thing.” It feels rigged when they tell you maybe you should just go pitch female VCs – as if there are that many of them! – because maybe they’ll ‘get it’. It feels rigged if you are the only female partner in your firm, and your colleagues assume you’re only bringing that deal to the table because the company is led by a woman.

Despite this, women are making progress all over the Valley, supported by a community of women that acts as a safety net for us all. Some are turning to crowdfunding, e.g. Naya Health’s Kickstarter campaign, and Genneve’s IFundWomen campaign. New models are emerging, like SheEO’s ‘radical generosity’ idea of women supporting women with low-interest loans and opening up their network.

When I first moved from London to the Bay Area five years ago to join X, I knew hardly anyone here. My new team consisted mostly of introverted engineers; it took them two weeks to even start talking to me. I was lonely, like I had never been before in my life. Silicon Valley is famous for its networking, and I wasn’t part of the network. I reached out to Nilofer Merchant, an author who had promised to introduce me to people when I met her. To my surprise, she came through. She organised a gathering of ten women at her house in Los Gatos. There was good food, good wine, and a henna tattoo artist. Nothing like bonding with strangers while having your exposed midriff painted with henna flowers… By the end of the evening, I felt I had known those kickass women for years. They welcomed me into their community, introducing me to other fabulous women, to the concept of going for a hike instead of going for a drink, and to brightly coloured Tieks ballet flats that look as good in the office as on a hike.

Why do we still need women’s networks?

When I first moved here, I had no idea how much I would come to appreciate this community of women. In Europe, I had never been part of any women’s group. In the Valley, they are an essential survival mechanism. Ask any woman; they are likely to be a member of at least one women-only mailing list, women employee group, female CEO breakfast club or women on board initiative. They attend women robotics meetups, tech talks and conferences. Grace Hopper Celebration, the biggest gathering of women in computing, grew from 500 attendees in 1994 to over 18,000 this year. Since that first dinner at Nilofer’s house, I have hosted women events at my house and at X’s offices to pay it forward, introducing great women to each other who came as strangers and left as friends or collaborators.

I turned from a latent feminist into an active feminist as I discovered how much Silicon Valley’s system is rigged against women. Fewer than 30% of tech industry jobs are held by women. Fewer than 20% of board members are women. Only 17% of startup founders and 8% of investment partners at venture capital firms are women. Less than 10% of venture capital goes to companies founded by women. Liza Mundy wrote a well-researched piece in the Atlantic earlier this year, ‘Why is Silicon Valley so awful to women?’, which I pay homage to in my title. When I sent it round to friends and colleagues, many women wrote back and said they recognised the patterns.

I’m an incurable optimist, so I see the events of the past six months as a sign that things are changing for the better. First, women are starting to speak out and fight back against the bro culture, perhaps encouraged by Susan Fowler’s blog post and the upheaval that followed at Uber. Second, men are stepping up to support them. It was painful for Google’s female engineers when their hard-won credentials were being challenged yet again in James Damore’s ‘manifesto’, but there were plenty of voices who supported them both inside and outside the company. My favourite rebuttal of Damore’s arguments is a Medium post by Xoogler Yonatan Zunger who points out that senior engineers need people skills to be good at their job, not just coding skills. Third, companies are more transparent about their diversity data and taking more of a stance. In 2014, Google were first in the industry to publish its diversity data, and got flak for having fewer than 30% women. When ten other major tech companies quickly followed suit, it emerged that 30% was the industry average. Many tech companies now publish their data every year; at least they are willing to be held accountable. Google did fire Damore for breaking the company’s code of conduct and reiterated its commitment to diversity on its diversity website.

Progress is frustratingly slow in the corporate tech world, but the venture world is moving at an even more glacial speed.

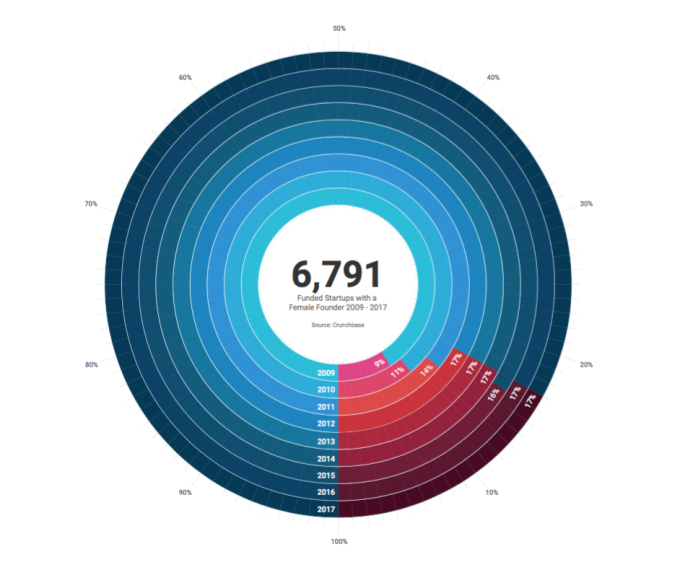

Source: Crunchbase, May 2017

Crunchbase has been tracking female founder representation of U.S.-based companies since 2009. Their 2017 Female Founder report found that the percentage of female founders stubbornly remains at 17%; there has been no increase in the past five years.

In 2016, Crunchbase’s first Women in Venture report found that only 38% of the top 100 venture firms had at least one female partner, and only 7% of the total partners were female. In their 2017 report it had increased to 8% female partners. Change is slow because established firms add very few new partners. The landscape is more likely to shift thanks to a new crop of VC firms founded or co-founded by women, such as Aspect Ventures, Cowboy Ventures and Forerunner Ventures. At firms founded in the past five years who have at least one female co-founder, around 50% of the investment partners are women.

I have been mentoring startup founders in Europe since 2001, but I only started focusing on women after I moved to Silicon Valley. European female founders are also in the minority, but they are not as isolated. First, there are role models. One of the most high profile founders of the early dotcom era was a woman, Lastminute.com’s Martha Lane Fox. She went on to become the UK government’s digital inclusion czar and now sits in the UK House of Lords and on Twitter’s board. Second, cities like London and Berlin are not dominated by tech. Female tech founders are surrounded by high profile female leaders in media, finance and politics. The US chose not to elect a female president, but Germany and the UK are led by women.

In Silicon Valley, the few women who do start companies are surrounded by a male-dominated ecosystem: The last generation of successful founders who are now redeploying their money are all men (Skoll, Omidyar, Musk, Page, Brin, Andreessen, Horowitz, Thiel etc). Most VC investment partners are men. Most startup board members are men. Women are not part of the boys club, and many find it harder to raise capital.

Janica’s story: A typical Silicon Valley female founder story?

One female founder’s story was recently told by Bloomberg’s Emily Chang and Ellen Huet under the headline “A Smart Breastpump: Mothers love it, VCs don’t. The New Yorker’s Jessica Winter was even more blunt: “Why aren’t mothers worth anything to venture capitalists?”

I first met Janica Alvarez in February 2014 at the Women 2.0 conference in San Francisco, not long after she had founded Naya Health to make a better breast pump.

Photo: Janica Alvarez/ Naya Health

I had only recently stopped breastfeeding my daughter, so my memories were fresh. The stress of finding time in my calendar for pumping sessions labelled ‘moo time’, trying to maximize milk extraction while checking my email. The awkwardness of storing my milk in the communal fridge, wondering whether somebody would accidentally put it in their macchiato. Schlepping my enormous pump to conferences, freezing the milk and hoping it would not get confiscated by airport security on the way home. The embarrassment of doing conference calls during pumping sessions when I was desperate to get the time back, hoping other people on the call would not notice the sound of the pump. At least my office did have a mother’s room. Many mothers are not so lucky.

All these memories came flooding back to me as I listened to Janica telling me how she was designing a better breast pump. A pump that was comfortable to use, as efficient and fast as a hospital-grade pump with the size and weight of an ordinary pump, beautifully packaged so you would not be embarrassed to carry it through an office or airport. I decided there and then to invest in Janica’s angel round, ignoring advice from a seasoned VC who doesn’t invest in baby product companies while his kids are small because his brain won’t assess them neutrally. I definitely wasn’t neutral. I really wanted this product to come into the world. My due diligence consisted of a cursory glance at Naya’s revenue and cost projections which were wildly optimistic like most early stage startups, and asking a friend who was still breastfeeding to test the pump. She confirmed that it was indeed both comfortable and fast, and became an investor herself. Since then I have been working closely with Janica as she went on her journey to turn the pump from a concept to reality, figuring out manufacturing, distribution, marketing – and fundraising.

Fundraising for Naya was difficult from the start. Janica was a first time founder, and working on a product that didn’t neatly fit into categories. Consumer VCs were afraid of a medtech product that required FDA approval. Medtech VCs were afraid of a consumer product that required retail distribution and mass marketing. Male VCs didn’t understand Naya’s product, saying they had to ask their wife or sister about it. Janica was initially reluctant to tell investors that her co-founder was her husband Jeff, in case they didn’t want to invest in a husband/wife team. I convinced her to lean into it, since it was part of Naya’s origin story: When Janica struggled with her breast pump, her mechanical engineer husband Jeff took it apart and said, “There must be a better way to design this thing.” After male VCs commented on her figure and berated her for not being home with her children, Janica started taking Jeff to investor meetings. This came at a price: investors would mostly talk to him during the meetings.

Of course Janica is not alone. Another wife and husband duo, Victoria Ransom and Alain Chuard, had the same experience when they were fundraising for Wildfire, their social marketing company that eventually sold to Google for $350M. Overall Victoria doesn’t feel that she was discriminated against because she was a female founder, but she noticed differences in VC behaviour: “Investors would ask Alain all the questions, even though I was the CEO.” Earlier this year, I hosted a small summit of 20 women startup founders in the women’s health and baby space. Some are working on products that are even harder or more embarrassing to explain than a breastpump. Surbhi Sarna of nVision Medical is working on a diagnostic tool for ovarian cancer that is inserted via the vagina. Jill Angelo founded Genneve to help women deal better with menopause, a topic nobody likes to talk about. Liz Klinger of Lionessmakes a smart vibrator to improve female sexuality. You can imagine how their meetings with male VCs went.

We need more female VCs, but that won’t fix the problem entirely.

Many female founders I spoke to were at some point advised to pitch to female angels or VCs. The problem is that there are not that many of them, and the story of who invests in female founders is much more complex.

Over the past 10 years angel groups and VC firms have been emerging that focus on women, many of them founded by women themselves. Angel networks such as Astia Angels, Pipeline Angels, Broadway Angels and Golden Seeds invest in female-led companies, and train women in investing. Frustrated with conventional models, Trish Costello set up Portfolia, an investment platform. Crunchbase lists 25 organisations and firms investing in female and minority-led companies. However, most of these firms invest at the early stage of the pipeline, with the majority of VC funds controlled by established firms who are mostly male.

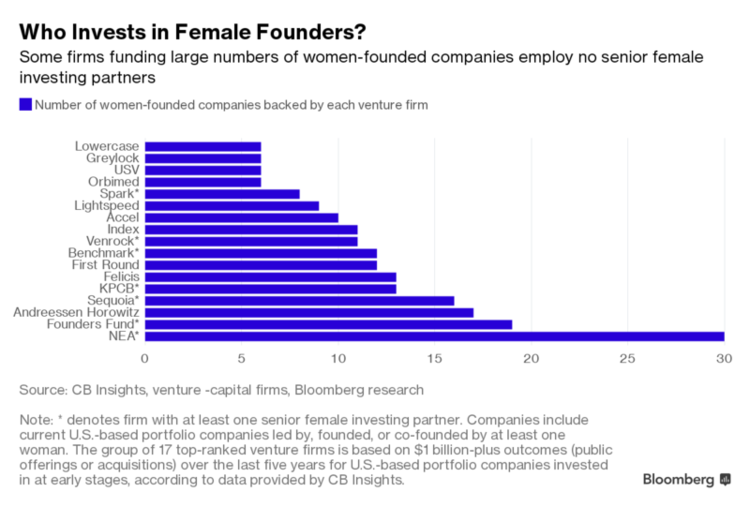

Interestingly, both Crunchbase’s Women in Venture 2017 report and analysis by Bloomberg found no evidence that firms with female investment partners are more likely to invest in female founders. In fact, Bloomberg found that some firms who fund a lot of women-led companies have no female partners at all.

Source: Bloomberg, May 2017

Some female VCs are passionate about backing women, such as Forerunner Venture’s Kirsten Green. Others say they look for the best deals, whether the founder is a woman or not. Many female VCs don’t want to be pigeonholed as funding women or products aimed at women, especially if they are the only female partner. Crunchbase found that this dynamic changes only if a firm has a lot of female partners: the small number of firms with an unusually high percentage of female partners do invest more in female-founded companies. This makes sense to me: If half the partners in your VC firm are women, you feel less self-conscious about bringing a ‘female deal’ to the table than if you are the only female partner in a male-dominated firm. Based on research in other domains such as corporate boards, my guess is that you need 30% female partners in a firm for it to change.

Alexsis de Raadt-St. James has no qualms about being pigeonholed. She set up Merian Ventures to explicitly invest in female entrepreneurs only. “My investment thesis of only investing in women is just good business, since female founders consistently produce better ROI.” I was curious why: Is it because it’s so hard for women to get funded in the first place, so that those who make it are exceptional? Or because women are underfunded?

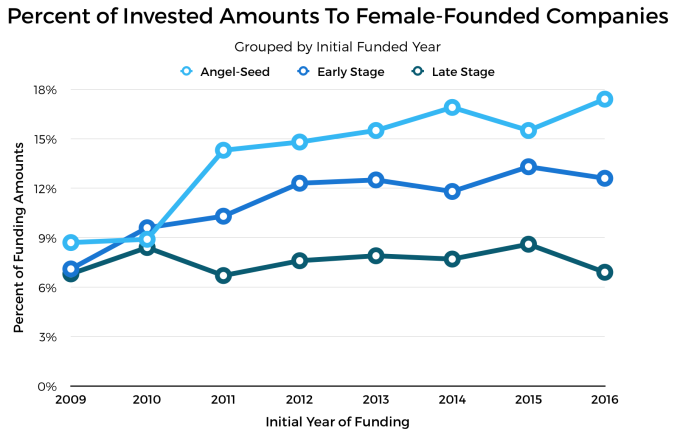

Women are underfunded, especially at later stages.

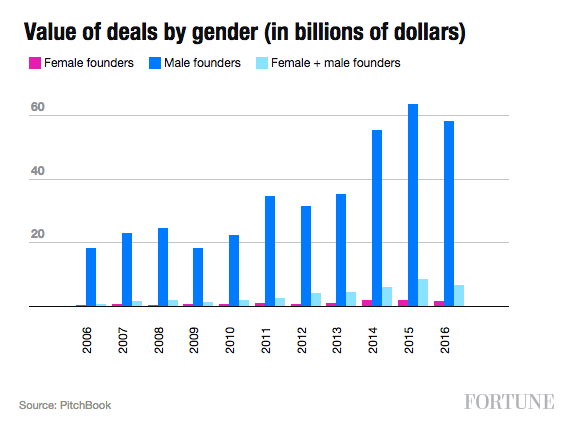

Fortune’s Valentina Zarya analysed Pitchbook data and found that 5% of 2016 deals involved women founders, but they only attracted 2% of total funding.

Source: Fortune, March 2017

Crunchbase’s analysis counts all companies with at least one female founder so it skews more positively. Companies with at least one female founder raised 19% of seed rounds and got 17% of seed capital. By late stage this had dropped to 8% of deals and 7% of capital, resulting in only $10B (9.6%) of total capital going to companies with at least one female founder vs $94B to companies with all male founders.

Joyus and Boardlist founder Sukhinder Singh Cassidy believes that women ask for less funding, just like they negotiate less hard for a salary raise or promotion. Kathryn Minshew, co-founder and CEO of career site The Muse, told Fortune that “in business, women tend to be judged on performance and men on potential. The same is true in start-up funding in aggregate as well. I felt that we had generally raised based on what we have done, while male founders raise capital on what they have the potential to do.”

Based on my own experience with female founders, I think Minshew has a point. I am on the board of Picasso Labs, an image analytics platform that uses machine learning techniques to predict how well an image will perform in an ad campaign or on a record cover. I have known the founder and CEO Anastasia Leng since she worked with me years ago. She is one of those people who always underpromise and overdeliver. This got her great performance reviews at Google, but I’m not convinced it is helping her fundraising efforts. Despite having run successful pilots with a long list of global clients including Unilever, Warner Music and Tesco, her VCs keep asking for more sales traction and more proof points. Would a male founder in her place have raised a Series A already based on the promise of their sales pipeline, instead of actual revenue? The irony is that she might not need the funding if her pipeline does convert, since the company would be profitable.

Janica Alvarez did eventually raise $6.5 million dollars in angel and seed funding for Naya, a much more modest amount than other hardware startups such as their competitor Willow or the now infamous Juicero. With this funding, Naya built the pump and companion health tracker app, got FDA clearance and launched last December. Investors were concerned about the $999 price tag for the pump, mothers were not. Naya sold their entire first manufacturing run of 1,000 pumps on their own website shop, on the back of great press (including WIRED and the New York Times) and word of mouth.

It was named by Fast Company as one of the top 10 innovations that made women’s lives better in 2016. Mothers gave the pump rave reviews, and shared Naya’s ‘If men breastfed’ video on Facebook and YouTube.

[su_youtube url=”https://youtu.be/Rko_jlXgiy8″]

Despite the launch success, Naya hit a wall again on Series A fundraising, partly because their seed round was funded by smaller investors who were unable or unwilling to provide substantial follow-on funding. New investors questioned the size of the market and whether Naya would be able to scale and compete with incumbents like Medela. Medela’s parent company had just bought Moxxly, another breastpump startup, for an undisclosed sum. One of Moxxly’s angel investors said in a Medium post that they sold to get access to Medela’s resources and broader reach.

Do we need an alternative funding model?

Perhaps venture capital is not always the right answer for these companies. It seems to me that there is a gap in the market for a loan product targeted to hardware startups who have launched their product and need money to scale manufacturing and distribution. Banks still consider this too risky, so perhaps the loans could be backed by the US small business administration. Or perhaps the loans could be backed by a community of women.

This is Vicki Saunders’ big idea. A Canadian entrepreneur and investor, Vicki founded SheEO in 2015 with the mission to “radically transform how we finance, support and celebrate female entrepreneurs”.

Photo: Vicki Saunders/SheEO

Vicki’s radical generosity model is centred around women supporting women. Activators commit $1,100 to a fund which provides no-interest loans to women-led ventures. The more activators pay in, the more ventures can be funded. Ventures are selected by the activators in an online voting process. Ventures have be at revenue stage, so they can start paying back the loan immediately to replenish the fund. In addition to the funding, which is still relatively modest since SheEO is at an early stage, founders get access to the SheEO network of activators and are encouraged to ask for help every month. They get advice and mentoring, introductions, first customers. I became an activator last year and it was a uniquely rewarding experience because I was able to stay involved with the ventures in a low-touch way. If I was having a crazy time at work and had no time to help that month, I knew that there were hundreds of other women who would step in.

“The goal is to get a million activators funding 10,000 women-led ventures with a $1B perpetual fund to support women for generations to come”, says Vicki at a SheEO event. “Are you in?” Her enthusiasm is infectious; 80% of the women in the room raise their hand. They have until November 1st to convert their pledge and become an activator in this year’s fund.

After months of trying to raising a Series A for Naya, Janica Alvarez turned to crowdfunding. She set an initial goal of $100k on Kickstarter to finance her next product, a smart bottle. Her Kickstarter campaign got over 200 backers in its first week, including women who don’t need the product for themselves but just want to support her. In response to this, she added a ‘women helping women’ pledge where backers can donate a breast pump to a mother in need. Jill Angelo also set up a crowdfunding campaign on IFundWomen.com for Genneve.

I hope that Janica makes her Kickstarter funding goal. Who knows, maybe there is even be a VC or banker out there who looks at Naya with fresh eyes and is willing to finance the next chapter of her story. And she will definitely apply to be a SheEO venture this year, now that she fulfils their revenue requirement.

How you can help.

- Janica has a Kickstarter campaign open until October 21st, 2017. (If you’re not in the market for a breast pump or baby bottle right now, you can donate a pump to a mother in need with the ‘women helping women’ pledge.)

- Genneve’s crowdfunding campaign is open until October 31st.

- SheEO’s 2018 fund campaign runs until November 1st. Become an activator. Men can’t become activators, but can sponsor a woman they know, or let SheEO pick one.

This article originally appeared on Linkedin and is republished here by permission of the author.

[su_divider top=”no” size=”1″]

About the Author

Obi Felten leads early stage projects at X, the team behind self-driving cars, delivery drones and internet from balloons. Previously she was director of consumer marketing for Google EMEA. Before Google, Obi launched ecommerce businesses and worked as a strategy consultant. Obi is a startup angel investor focused on women founders. She is on the board of Shift, a charity, and Picasso Labs, a tech startup. Obi grew up in Berlin, went to Oxford University, and lives in San Francisco with her husband and young children.