He decided to look at the facts.

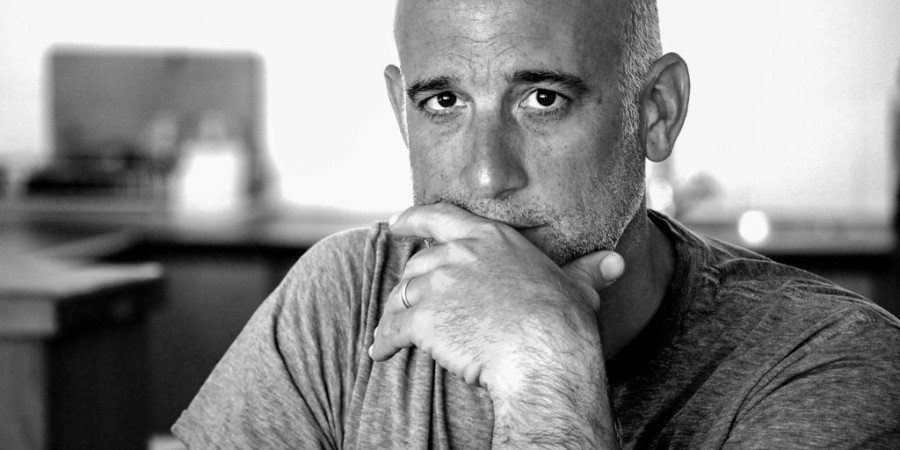

When Pete Gombert was building his third technology company in 2010, an article about pay inequality caught his eye — and sparked some important questions for the serial entrepreneur.

“I’m an accountant by training and have always been very, very curious about numbers,” Gombert said. “I wondered if we had an issue in our organization, which had probably 120 employees at that time. Were women being paid less?”

Deciding to investigate, he armed himself with the company’s pay data and went to “run some numbers.” But he didn’t get very far, at least initially.

“I found there was no accepted methodology to even measure the gender pay gap for a single, individual company,” Gombert explained. “Most of the statistics that we see end up being macro-level statistics; they’re not really built on this micro-level for organizations. So I had to go and develop a methodology.”

Eyes opened!

New methodology in hand, Gombert was able to hit the books once again — and what he discovered was extremely troubling.

“I found that we did, indeed, have a gender bias when it came to pay, which was particularly disturbing to me because I had hired and negotiated contracts for every person in the company,” he said. “This meant I had either intentionally created this bias — which, I can assure you, I did not — or that I had an unintentional bias that came into play as I was negotiating these contracts.”

All in all, the experience opened Gombert’s eyes to not only the harsh reality of unconscious bias, but also the way a metrics-driven approach be used to ferret it out. Out of this discovery, his company GoodWell was born. Today, the folks at GoodWell are using Gombert’s methodology to help employers analyze their own inclusivity and ethics, scoring companies on a rubric comprised of 11 key healthy workplace indicators. And when he’s not advising organizations on how to most fairly treat their talent, the entrepreneur has some ideas for how men can ensure fairness for female coworkers in a more lateral sense, too.

To best be allies to women colleagues, Gombert recommends that men do four things:

1. Be aware.

“Measure what matters,” Gombert advised. “To me, I’m a numbers guy, so having some metrics that help you understand how your behavior is impacting others and whether your behavior is in line with your intentions is critical.”

At GoodWell, one way Gombert seeks to accomplish this is by using an employee “net promoter score” for all organizations that apply for the company’s seal of ethical approval.

“That simple step is really powerful in being able to identify where you have systemic harassment, leadership, communication, and pay issues,” he said.

2. Implement a protocol for employee feedback.

“Create a systemic environment of continual feedback so that you can identify these kinds of issues happening before they get out of control,” he said. “Put into place a system that allows you to systematically gather that feedback, and have it be both qualitative and quantitative.”

Gombert advises that allowing for anonymity can be useful here, but that many such pre-existing tools — like third-party harassment hotlines — aren’t well utilized. This is potentially because employees aren’t fully aware of the resources at their disposal; to that end, not simply having a feedback protocol but also educating people on how to access it is crucial.

3. Reject passivity.

Pointing to the recent Harvey Weinstein scandal, Gombert spoke to how pivotal it is that men (as well as women) become active participants, not simply bystanders, in eliminating these kinds of behaviors.

“The fact that we allow (harassment like Weinstein’s) to happen is unconscionable, but I think what leads to that, quite honestly, is probably the bigger problem, which is what I call an environment of passive abuse,” he said. “It’s the things that happen every day, like where people say things that are considered ‘jokes’ but still make people uncomfortable. And yet, by and large, we don’t see men or women standing up and saying, ‘That’s not right, you can’t say that’… It’s the little things that permit the big things to happen.”

4. Encourage a culture of sharing and transparency, for all genders.

Of course, no one feels empowered to reject so-called passive abuse when a culture of shaming and toxic masculinity is present within a company. Therefore, Gombert’s last bit of advice is potentially the most imperative — that a precedent must be set for standing up, speaking out, and being supported.

“We certainly can’t have people afraid they’re going to jeopardize their career for calling out bad behaviour,” he said. “For men, there’s this fear that, because we’re brought up in an environment where we’re very egoic and have to put on this air of being manly, that if you do speak up and take a position that defends women, then you’re a pariah to the standard male view. And men are afraid that could diminish their careers.”

For the Harvey Weinsteins of our time to be truly be eradicated, that fear of ostracization must be replaced by a new standard of behavior for men. And male leaders can play a crucial role in cultivating that, Gombert said.

“As soon as leaders start making it clear that these things aren’t okay, then it becomes okay for everybody to say that,” he added. “To the extent that anyone reading this is in a leadership position and can model their behavior and make it clear that (toxic masculinity) is not okay, that goes miles and miles.”

This article originally appeared on Fairygodboss and is republished here with permission.