This article originally appeared at Forbes on its leadership blog.

I recently saw a job posting whose first bullet point under the list of required skills and experience was “Bachelor’s degree from a top university.” This is not an uncommon selection criterion, even when it is not explicitly stated in a job posting: a 2012 eye-tracking study by The Ladders shows that “education” is one of the top items reviewed by professional recruiters when scanning a résumé.

Whether your firm does it purposefully or involuntarily, focusing your recruiting efforts on top universities may be one of the biggest mistakes you will make in finding the best talent for your company. Here are five important reasons.

#1 College performance does not translate to job performance.

The assumption that education correlates with on-the-job performance is unfounded. In fact, an authoritative study on the value of different personnel selection methods found that education-based measures correlate very poorly with on-the-job performance. Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that the selection processes and criteria used by universities have anything to do with the characteristics that make one a successful employee. The selection process of even the best universities will reject some potentially excellent candidates while accepting less promising candidates, simply because their criteria are very different from those of your company.

#2 You overpay for talent.

Hiring students from top schools can be very expensive. PayScale and the U.S. Department of Education, respectively, have published data from thousands of U.S. Colleges reporting median salaries for their alumni early in their career, or six years after graduation. Using the list of best colleges in the U.S. as ranked by U.S. News, we can compare data from the top ten and the bottom ten colleges on the list, i.e., those ranked 1-10 and those ranked 91-100: early in their career, the median salary for graduates of the top ten colleges ($72,160) is 31% higher than the median salary for the bottom ten colleges ($55,160). By the sixth year, this gap has nearly doubled to 58%. And this discrepancy is much higher when looking at colleges below the top 100. As an example, the PayScale dataset shows the average early career salaries across the top 10 colleges within the CUNY school system at $48,960, making recent graduates of the top ten U.S. News colleges a whopping 47% more expensive than CUNY graduates. At the 6-year mark, that gap jumps to 108% – in other words, that Columbia alumna is costing you more than two CUNY alumnae (disclaimer: I have a part-time position at The City College of New York, a CUNY school).

#3 It’s a bad idea to compete for a scarce resource.

Perhaps you are thinking that the Columbia alumna is worth the extra money. If so, you should remember that the cost of an item is directly proportional to its scarcity. Insisting on hiring from top schools is like insisting on buying airplane tickets when there are only a few seats left: you pay more and only find middle seats. The top 50 U.S. News colleges, in aggregate, have roughly 600,000 undergraduate students – only 3% of the 20 million undergraduate students in the U.S. And with job placement rates that often surpass 90% for the more coveted fields such as business and engineering, unless you can afford the luxury of wasting money to pay absolute top dollar, you will likely get an average student from a top school, but still pay much more than you would for top students from an average school.

#4 You risk missing out on some great talent

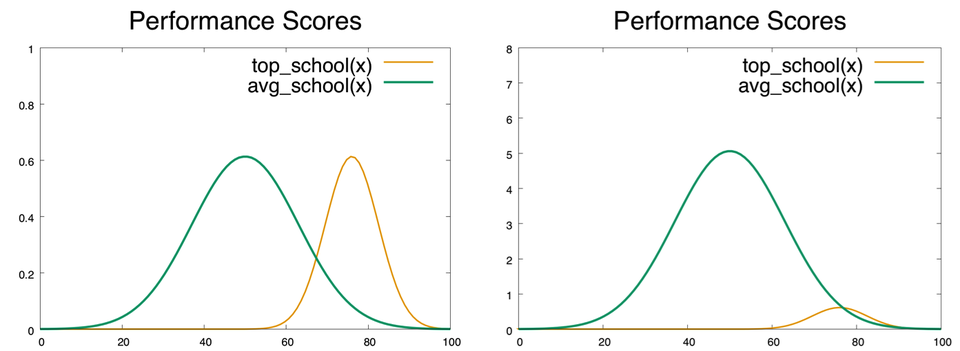

The previous point begs a question: is an average student from a top school better than a top student from an average school? Suppose you had a magic wand that could give you the “performance score” of any candidate from any university, which perfectly predicts how successful that candidate will be in your company. Across any population, you would expect these scores to follow a bell curve. Let’s assume that the population of students in the top 50 U.S. colleges has much higher scores, and much less variability in the scores, than all other students. The figure below helps us to visualize a possible scenario.

P. Gaudiano

P. GaudianoHypothetical bell-curve distributions of performance scores for students from the top 50 colleges (thin yellow curve) and all other schools (thick green curve). Top-college students are assumed to have average performance two standard deviations above the mean of all other students. Left: normalized hypothetical distributions. Right: the same distributions scaled properly to reflect the respective student population sizes. (Images created by the author.)

The left graph in the figure depicts an example in which the average student at the top 50 colleges outscores 98% of the rest of the U.S. student population, while the variance in scores for the top 50 colleges is half of the variance for all other students. But even in this extreme scenario, you have to take into account that only 3% of the population attends these top 50 colleges, which means that the bell curve on the left should be much taller. The graph on the right side of the figure shows the proper distributions of scores adjusted for population size. Clearly, there are many students from the non-top schools that outperform the students from the top 50 colleges. In fact, 2% of the overall population (about 400,000) perform better than the 300,000 top-50 students who are better than average relative to their own peers. And while almost all 600,000 of the top-50 students will have scores above 65, so will 3 million of the non-top-50 students. In other words, even under these extreme assumptions of top-school superiority, you are ignoring a much larger pool of candidates from lesser schools with the potential to outperform many of the candidates from the top schools.

#5 You are perpetuating systemic biases.

Finally, one of the most troubling aspects of focusing on top schools is that students from ethnic minorities are underrepresented at top schools. For example, drawing again from the U.S Department of Education, we find that only 4.7% of students at the top 50 colleges identify as black. By comparison, 18% of students at the top 10 CUNY schools identify as black, while the nationwide average is 14%. Anyone who appreciates the business value of diversity should think carefully before deciding to recruit from top-ranked schools, because in so doing they are shrinking their own talent pipeline and implicitly favoring the privileged segments of the population.

There are other reasons why focusing your recruiting efforts on top schools is not a good idea, but hopefully the five points above have convinced you. If so, consider reaching out to career services offices at schools in your area, look for events attended by larger numbers of students (such as the forthcoming conference and job fair I am helping organize at CUNY), advertise in student newspapers, and generally keep an open mind. Even from a purely statistical perspective, your next superstar is much more likely to be attending one of the lower-tier schools, but she or he will never even know that you exist unless you make the effort.

Please subscribe to my newsletter and visit Aleria and QSDI to learn more about my work on diversity & inclusion. And please check out my earlier blogs.