The most frightening moment of my life was the day I walked into “Introduction to Women’s and Gender Studies” during my sophomore year at Saint Mary’s College in Moraga, CA. Born and raised as a Latino male, I quickly learned the rigid expectations and boundaries of masculinity and the social expectation to follow every aspect of it. Walking into that class and later deciding to double major in Women’s and Gender Studies and Sociology were conscious acts of resistance to these rigid, toxic gender expectations of masculinity. Little did I know that these decisions would not only help me discover my true self but also lead to an unconventional career shift to recruiting underrepresented executive talent in Silicon Valley.

Here I was, a naïve, somewhat cocky 20-year-old at the time, thinking I had my life figured out. I had plans to finish college with a Criminal Justice degree by 22, become a police officer by 23, make Sergeant by 30, marry my wife and have kids by 33. Happily ever after. I had goals, but in the back of my mind, I was still struggling to understand my past and who I was as a young Latino man. I didn’t play football or soccer in high school — I played volleyball. I wasn’t tough, emotionless, or a conduit of “machismo” in my family and community. I didn’t go to high school parties or hang out with the boys every weekend. I gravitated towards friendships with women, and I ended up building stronger relationships with them and the women in my family. Frankly, I was often bullied because I showed emotion, played few sports, spent more time with women, and didn’t fight back when opportunities arose. The reality is that I felt different, and I never had a language through which to understand and express my unique experience as a young Latino man who never seemed to fit in.

Women’s and Gender Studies (or WaGS, for short) was my last hope. It was hard to walk inside that classroom, for I knew this was the first step in confronting the anxiety and pain that I had been experiencing my entire life until that point. To no surprise, I walked into a room filled with women, most of them looking at me with a confused, curious expression on their faces. I turned out to be one of only three men in the room.

Without diving into three years’ worth of feminist theory, let me put it this way: WaGS opened the door to understanding the inner workings of traditional masculinity, how it’s both influenced and challenged by social forces that work together beyond my control — for example: mass media, race and ethnicity, socio-economic status, sexual orientation, location, peer groups, age demographic, and so on. Put simply, all those years of being bullied and ostracized led me to realize that I did not express masculinity in the typical fashion that society unconsciously respects, understands and validates. Through my studies, I finally had the lens to understand and contextualize my lived experience, and I made peace with past experiences with masculinity.

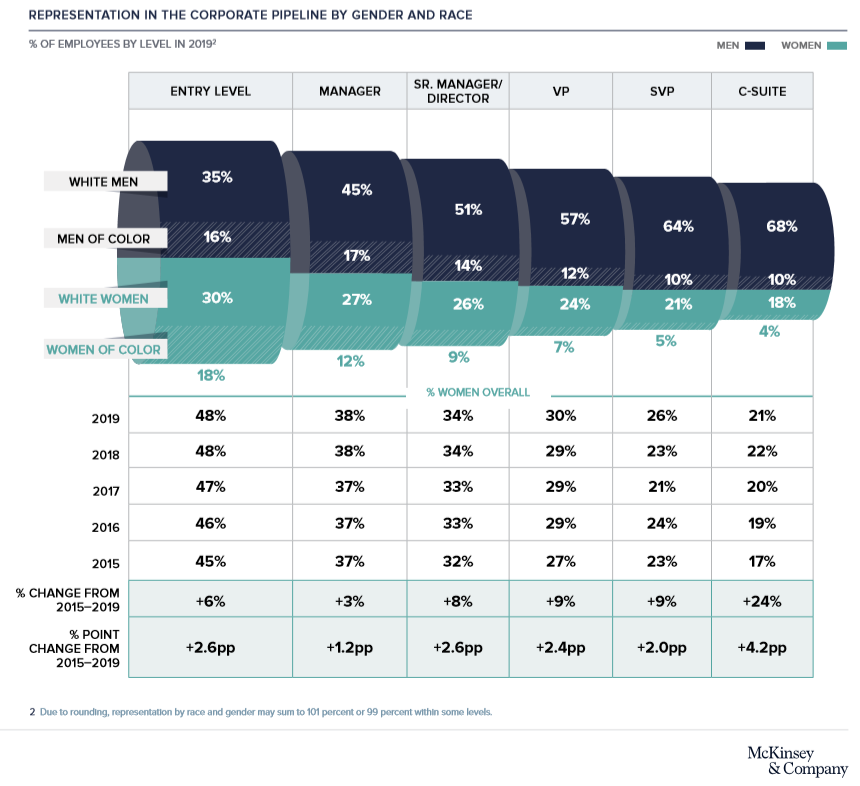

Alongside this revelation, I also learned that as a man, I benefit from certain privileges: such as getting paid roughly 2% more in salary than women when looking at the controlled gender pay gap in 2019. Privilege also comes in the form of unequal opportunities for men over women, especially when you factor in race alongside gender. Although incremental progress has been made in diversifying senior leadership teams since 2015, according to McKinsey’s recent “Women in the Workplace” report, we are far from gender and racial parity.

When defining “executive” as the range between “Director” and “C-suite,” men of color hold 11.5% of executive positions, while women of color hold roughly less than half, at 6.25%. To no surprise, the actual percentage of men and women of color per level decreases as you move up the ranks to C-suite. For example, as noted above, women of color hold 9% Sr. Manager/Director, 7% VP, 5% SVP and 4% of C-suite roles.

Why does this all matter? Aside from the moral aspects of doing diversity and inclusion work, tackling this specific inequality in executive leadership is now my job, one that I feel uniquely positioned to address thanks to my WaGS experience. Allyship was a foundational topic I learned throughout the major, and it’s one that has given me continual guidance in my work. D&I leader, Sheree Atcheson perfectly captures this sentiment:

“[allyship is a] lifelong process of building relationships based on trust, consistency and accountability with marginalized individuals and/or groups of people.”

I’m now an executive recruiter at a cloud company in Silicon Valley, where I lead efforts to recruit underrepresented talent into our executive ranks.

WaGS taught me how to deconstruct and analyze social and institutional forces surrounding the hiring practices of tech companies in Silicon Valley. In addition, I’ve challenged myself to actively use my role as an ally in helping advocate for racial and gender parity in the talent pipeline. On an individual level, WaGS helped me understand how best to practice allyship in the workplace to my female colleagues.

Lately, I’ve been feeling hopeful about the tech industry’s direction regarding diversity work in light of the #MeToo movement. I have met several male executives that are ready to challenge themselves to do the uncomfortable, deeply personal work necessary to be a better leader through allyship. I constantly remind myself that allyship is a verb and not a noun. As men, we all must practice and commit to this work daily if we’re ever going to accelerate the progress already being made regarding diversity. Attending one unconscious bias training on a random Tuesday morning and receiving your “Certificate of Completion” that same afternoon is not going to cut it.

I’ve been working in the tech ecosystem of Silicon Valley for four years now, and I’ve seen several areas where we as male allies (specifically men in leadership positions) can better support women and other underrepresented people. On a foundational level, male leaders must understand diversity not as stand-alone identities such as “woman” or “Latino” or “Black;” rather, they must view diversity as a multi-dimensional, interconnected web of identities that overlap to create unique experiences, otherwise known as intersectionality. Following this understanding, men must take on more of the emotional labor associated with advocating for inclusive policies, gender and racial parity in senior leadership, pay equity, accountability during quarterly business reviews, and other critical areas of diversity and inclusion work.

Male executives can also directly tackle the opportunity gap by taking more time to mentor emerging leaders that are women and people of color. Believe it not, I’ve read cases where some men, fearing possibilities of sexual harassment allegations, fear mentoring women altogether. Now more than ever before, male leaders must act as allies and address this discomfort head on. Funneling more resources to talent development will help support the leadership growth of underrepresented talent and directly address the largest obstacle to women on their paths towards becoming executives: reaching their first manager position. McKinsey has identified this “broken rung” in the executive talent pipeline as a major issue, one that is significantly decreasing the number of leaders who are women or people of color.

Leaders who take an empathetic approach towards management and seek to understand employee needs in the context of business needs will unlock their organization’s true potential. Alongside this approach, men who proactively work towards using their privilege to elevate others will be well-equipped to create teams that value true inclusion and significantly reduce unconscious bias. Ultimately, these efforts will create a sustainable organization that fosters ‘belonging’ amongst employees of underrepresented backgrounds and better understands its diverse customer base.

The holistic goal should be extending male allyship that transcends the workplace and permeates the core of who we are as men. How can we be better fathers, grandfathers, husbands, boyfriends, sons or uncles to the people in our lives? How did we get to where we are today and what can we do to uplift others who don’t have the same privileges as we do? I ask myself these questions and keep these practices top-of-mind as an ongoing ally, who so happens to also be in the business of recruiting executive talent.

Allyship takes courage and a willingness to listen and learn from others’ perspectives. I took the first step by walking into that first Women’s and Gender Studies class. Since then, I’ve been actively practicing my allyship skills. I’m ready and willing to take that first step again, for what’s to come down my future leadership path. Are you?

This piece originally appeared on Medium, and has been republished with permission.