In December 2021, I quit a six-figure job at a prominent tech company to set up an early-stage venture capital firm to leverage and scale my angel investing track record and deal flow. I’ll share my experiences and learnings, specifically, the mistakes to avoid, barriers you’ll encounter, and how the system is set up by taking you on my journey raising a fund. I’ll share real conversion statistics, a market map of where to find investors, and how you can navigate the investor (often referred to as an LP or limited partner) landscape as an emerging fund manager.

Don’t get me wrong, I love the grind of raising a fund but let’s start with a meme of what it was like to be in the driver’s seat of starting a venture fund….

Learn the rules of the game

In 2018, I lost a game of Monopoly to my 13-year-old sister on a technicality. I’d spent the entire game accumulating and building a slew of sewage works near all her properties because this would reduce the rent owed by 50%. My strategy was simple, let her waste all her money on properties and make them all worthless by building sewage works beside them.

7 rounds in and my strategy had failed woefully after she’d decided to build a stadium which nullified any sewage works I’d built across all her properties (yes Monopoly is now super complicated folks).

“Tough luck, you should’ve read the rules,” she said with a churlishness that only a savvy Gen z could dispassionately dispatch with such brevity. My 15 sewage-strong empire crumbled as all my cash flow lined the pockets of an unscrupulous 13-year-old who’d understood the rules of the game.

Before I began my quest to start a venture capital (VC) firm I was determined not to lose in the real-life version of monopoly (aka capitalism), and so I set out to learn the rules of the venture capital game. Let’s start by looking at the regulatory considerations of setting up a VC firm.

To raise publicly or not to raise publicly? That is the question.

There are two ways to raise VC funds. A 506b whereby a fund can’t publicly declare it is raising a fund or a 506c whereby a fund can publicly solicit investors.

The most detrimental piece of advice I’ve received to date was to raise my fund in private via a 506b and not publicly with a 506c. Although I was given this advice with the best of intentions, it easily set me back months if not years. Why? Well raising in private means you are essentially locked into raising from your own personal network. I can’t speak for most emerging fund managers but unless you are in the top 5% socio-economically, the chances you’d have 25–40 individuals in your network that can write a $100k check with no liquidity for 10 years seems improbable Perhaps if you grew up in an affluent neighborhood where your college friend’s dad was a C-Suite executive, otherwise, your chances are slim to none.

In short, you must raise publicly and go outside your network by proactively reaching out to a specific pool of accredited high-net-worth individuals who’d be willing to be limited partners in an emerging fund. LPs often prefer 506b funds that don’t raise publicly because otherwise, they may need to share personal documents to prove they are accredited investors. No one likes sharing intimate financial details, which poses a chicken and egg situation for emerging fund managers. Raise publicly and your risk losing investors because of privacy, or raise in silence with limited reach beyond your immediate network.

Establishing relationships outside your network, especially those deep enough to warrant six-figure capital inflows takes time. After all, would you give someone you met three months ago $100k from your savings? Probably not. If you aren’t well connected to an affluent group of people through your education, neighborhood, or professional network your chances are extremely slim. Even though I was armed with a graduate degree from Berkeley, and an extensive network across tech and VC in the Bay area, London, and New York, my network still primarily consisted of unaccredited investors who aren’t able to participate in the fund.

Emerging venture funds are overwhelmingly raising publically. In many cases, they must leverage their large social media following as a funnel to raise awareness of their fund amongst an audience of accredited investors. Linkedin, Twitter, and newsletters all serve as prospect funnels, none of which can be leveraged unless you raise publicly as a 506c.

My best estimate directionally indicates that more than 65% of funds that were successfully closed were raised publicly over the past few years. You’ll be raising for the next 5 years unless you become part of an exclusive network of high-net-worth individuals, and so, in essence, you have no choice but to raise publicly.

Accreditation rules prevent, ahem, I mean “protect” investors from investing in emerging funds

The accreditation rules prevent emerging managers from accessing pools of capital because fund managers can only raise funds from accredited investors.

An accredited investor is an individual who must have earned an annual income of at least $200k ($300k for a joint income household) in the preceding two years with the intention of generating the same or a greater annual income in the current year.

This begs the following questions:

- Why is wealth the determining factor in what you can invest in instead of the ability to judge good investments? Someone who makes $200K a year running laundromats is arguable a less sophisticated investor than an analyst at an investment bank who makes $100k per year.

- Instead of “protecting” unaccredited investors aren’t these rules blocking unaccredited investors from funneling a portion of their capital to capital-starved startups? After all, these individuals are trusted with the responsibility and freedom to gamble, raise children, and go to war for their countries but not write a $5k check to a startup?

What are the ramifications of the accreditation rules?

- Emerging managers are locked out of large swaths of capital from unaccredited investors.

- Funds invest in startups that are aligned to the wishes, tastes, and sensibilities of their LPs ( Limited Partners ) aka the kingmakers ( more on that to come but this concept is called enmeshment).

- Reinforced wealth gaps between the wealthy ( aka accredited investors ) and everyone else.

- Inefficient flows of capital. Capital flows are largely the result of closed networks as opposed to great ideas.

On a personal note, the irony is that I met the accredited investor criteria as an employee at a large tech firm just a few years ago, but now that I am an emerging fund manager I am currently unable to invest in my own fund.

This system of accreditation was either intentionally designed this way or is one of the most ardent examples of unintended consequences and market failure.

The modern kingmaker

The English Monarchy was overthrown in 1649 upon the execution of King Charles the 1st. Just 11 years later, the monarchy was restored and moderated by an independent parliament. Over the next couple of centuries, civilizations across the world decided that a system of Kingmakers didn’t promote prosperity as widely as possible.

Fast forward to modern society, and although I’d like to believe we’ve put paid to centralized economic models, the system is more centralized than we’d like to believe. Some might even say we have a modern monarchy reinforced by free markets in tech and VC. The goal of a functioning tech ecosystem and economy is to funnel the most money to the best businesses in the most efficient manner possible. Sadly the current setup comes a bit short of reaching this goal.

The internet is a prime example of how kingmakers determine the winners in a competitive market.

The internet was founded as an open marketplace where anyone can set up shop and provide a service to the millions of consumers scouring the internet for solutions.

More often than not, consumers purchase the first solution they stumble upon or they’d end up spending weeks researching and analyzing hundreds of vendors that can solve their problem, but what are the chances of a small business ranking near the top of any Google search?

Too often, the internet businesses that win are those that have millions of dollars to advertise within the first 3 lines of any given Google search seen by 99% of consumers. After all, studies suggest less than 5% of users go to the 2nd google page.

In short, a mom-and-pop business has very little chance against a VC-backed company that can fund its way to the top of the google search results with copywriters, ads, and world-class SEO. Venture capitalists have become defacto kingmakers because the startups they chose to back become category winners more often than not. This is simply a function of them outspending competitors on customer acquisition.

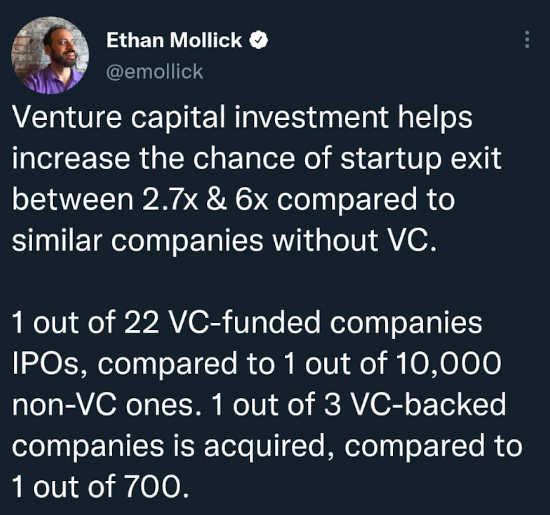

The effects are magnified a the IPO stage as well with VC backed firms having better odds of success.

Similarly to internet businesses, as an emerging fund manager, I too rely on a set of Kingmakers to back me if I am to have any hope of being top of mind for the LPs making emerging fund investments. It’s not the fund manager with the best deal flow, thesis, or team that ultimately gets funded. Often, It’s the emerging fund managers that can find and convert the most limited partners. That’s the uncomfortable truth. To become a kingmaker of startups I must be selected amongst the kingmakers of kingmakers i.e. limited partners ( LPs ). A feat 10x harder than I imagined.

According to Samir Khaji, CEO of allocate

“We consistently saw LPs invest in emerging managers based solely on feel, first-degree network introductions (thus limiting the supply pool), and not having enough diversification across managers”

Like the first page of Google’s search results, first-degree connections of LPs networks play an outsized role in who gets funded. A far cry from an efficient system to allocate capital to the best ideas, businesses, and entrepreneurs which could come from anywhere.

These kingmakers of venture capital fund managers come in the form of institutions, family offices, endowments, and high-net-worth individuals. They are often referred to as LPs or limited partners.

The kingmaker’s tastes

To beat an old cliche to death, let’s start with one of my favorites: “The customer is always right”.In this case, the kingmaker is always right. So what exactly are the preferences and tastes of Limited Partners? The majority of LPs prefer funds that invest at one stage of a startup’s lifecycle and have a sector focus.

Most fund managers can and should have a sector and stage focus that aligns with the tastes of most LPs.

In many cases, however, emerging managers diverge from the tastes of LPs.

Challenges for emerging fund managers

1. Fewer dollars are available for emerging managers.

The percentage of VC funding that goes to emerging managers has hit a decade low and is currently less than 5% of all VC dollars raised. In essence, limited partners are opting to back established funds.

While LPs have steadily allocated a diminishing portion of their capital to emerging funds, their top frustration was that the size of the funds they invest in is too large.

Why would LPs be frustrated with fund sizes yet allocate more capital to larger funds?

Well, most are looking for safe sure bets ( even though the returns are lower ). Larger VC funds know this and so they have fewer incentives not to raise the largest fund they possibly can. In the end, emerging managers are left with an ever smaller allocation of the LP’s portfolio.

2. Emerging funds are too small for LP check sizes.

Institutions often have large minimum check sizes ($5M, $10M + in most cases) however they often want to stay below 10% of the total fund. Essentially this locks out most emerging fund managers who must raise at least $25M to $50M dollar funds minimum to get institutional capital.

Given fund managers are expected to invest 1% of the total fund from their own pockets, you must essentially have $250k to $500k under your mattress, a tall order for most emerging managers.

3. LP pattern matching makes fundraising harder for emerging fund managers.

Limited Partners stress track records as a major factor in making investments. The goal is to assess if the fund manager has a pattern of success or if his or her success is a one-off. Pattern matching however is often a double-edged sword because if you don’t look like a typical fund manager you’ll be pattern-matched out of consideration for investment.

Minorities and women are often not viewed as typical fund managers which is an added barrier to raising a VC fund for the first time. This applies to other differentiators like non-ivy league graduates, folks from rural areas, and many groups.

To make this more concrete, let’s look at pension funds. Pensions have $35 Trillion in assets under management of which at least $3.5T ( and that’s a very conservative figure ) was collected from women and minorities through their 401Ks. Less than 1.3% ( $455B ) of all assets managed by pension funds are managed by female or minority fund managers. In essence, minorities contribute more than their fair share and are in a $3T surplus.

Why are women and minorities and women good enough to take money from yet not good enough to invest in? One reason is that decision-makers often invest in people that look like themselves because they have examples of success from their communities they can point to and draw conclusions on the patterns of success.

Pattern recognition plays a role in who gets funded and who doesn’t. In fact, SEC research shows that founders are 21% more likely to be funded by an investor of the same ethnicity than of different ethnicity. This same dynamic plays out at the institutional LP level too.

“We find evidence of racial bias in the investment decisions of asset allocators, who manage money for governments, universities, charities, foundations, and companies. This bias could contribute to stark racial disparities in institutional investing. In general, asset allocators have trouble gauging the competence of racially diverse teams. At stronger performance levels, asset allocators rate White-led funds more favorably than they do Black-led funds.” SEC

Some limited partners understand that pattern recognition at times doesn’t serve their interests. For example, according to the knight foundation

Institutional investors, such as pension and endowment funds, have an obligation to invest their money wisely. This can — and should — include working with women- and minority-owned and managed firms. There is no reason not to do so,” said Juan Martinez, Knight Foundation chief financial officer.

A fair number of fund managers are former employees at VC funds. Their ability to pattern match based on their experience could be an asset but pattern matching equally reinforces who gets hired at venture capital firms in the first place.

When institutions do allocate funds, the vast majority do not invest in funds with decision makers that reflect the populations they have taken funds from ( in the case of pension funds, etc ). This poses a problem because the Managing Partner of an emerging firm is often an ex-employee of a larger firm.

For context, the U.S. population is 57.8% white, 18.7% Hispanic, 12.4% Black, and 6% Asian. While equality of outcome shouldn’t be the goal but rather equal distribution of opportunity, this does pose a challenge, especially in the context where we have a young, mostly brown permanent underclass and a wealthier older mostly white investor class.

4. LP engagement and response rates are extremely low.

High net worth individuals and family offices are the majority of an emerging manager’s LPs. Networking with these two groups is absolutely necessary, and is often the only way you’ll be able to close your fund because it is very relationship based, however, it is very time-consuming.

As an emerging manager, your most precious resource is time. Finding scalable and digitized ways of finding LPs is crucial. It’s especially challenging to form these relationships digitally because of the low engagement rates across different platforms

Below I’ve detailed the results of my effort to raise from private individuals, funds of funds, and family offices.

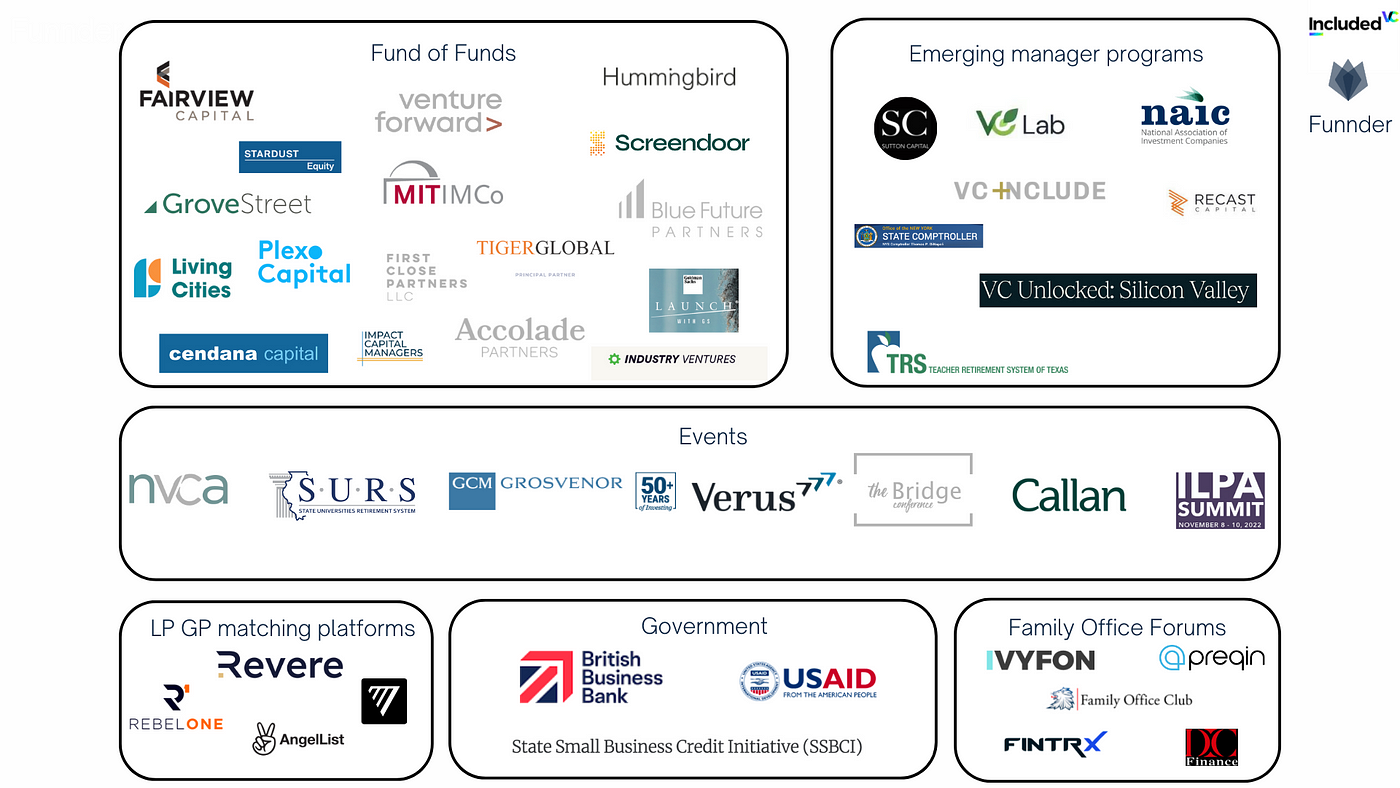

Before we look at the stats, let’s take a look a the LP landscape as a whole. This is the top-of-the-funnel exercise fund managers must painfully map out before they engage.

Over the course of a few months, I’ve reached out to each of the groups above with varying degrees of success.

Emerging Manager Programs

- VC lab: Accepted

- Sutton capital: Accepted

- Equity alliance: In discussions

- VC include: Semifinalist

- First close partners: Rejected

- Recast capital: Rejected

- Plexo capital GPx: Awaiting a response

Fund of funds ( all reached out to via Linkedin or email )

- Tiger global: Awaiting a first response

- Screendoor: Responded, no investment ( reason given )

- Blue future partners: Responded, no investment ( reason given )

- Summit peak: Awaiting a first response

- First close partners: Rejected

- Next play capital: Awaiting a first response

- Callan: No response

- Weathergage capital: Awaiting a first response

- 776: No response yet

- CrossCreek: Awaiting a first response

- Stafford capital partners: Awaiting a first response

- Invesco: Awaiting a first response

- Fairview capital: Awaiting a first response

- Cendana capital: Awaiting a first response

- GCM grosvenor: Awaiting a first response

Linkedin Outreach ( Across family offices and funds of funds )

- Linkedin Contacts: 1002

- Responses:69

- Investors:1

- Linkedin page followers 136

Email and newsletters

- Emails sent: 500+

- Newsletters:5

- Response rate <2.5%

- Investors LPs:1

Conclusion

It takes a tremendous amount of effort to raise a fund. Recommendations and conclusions for emerging managers

- Unless you are well connected to accredited investors, raise publicly and have a specific stage/thesis.

- You’ll have more luck if you focus on Limited Partners that look like you or have similar experiences/backgrounds as you(it’s not pleasant but it’s the truth)

- Reaching out to LPs digitally only won’t get you to your funding goals. You must network face to face as well.

- Limited partners are increasingly drawn to larger more established funds that meet their check size and risk-return profile. Find out your LP’s needs and either meet them or move on quickly.

- Don’t give up! (I’ve not even done my first close but I’ll get there soon ).

This piece originally appeared on Medium, and was published here with permission. Listen to and Subscribe to the Saka’s is that so Podcast to hear from other emerging fund managers.