Fair Salaries: The Struggle Is Real

For HR leaders, especially those who focus on talent acquisition, making fair and equitable salary decisions is a daily struggle, and one that can frustrate even the most experienced leaders.

It is common practice to make compensation decisions based on salary history. When considering costs and the bottom line, companies are often tempted to leverage opportunities to pay as little as possible for a role, offering whatever a candidate will accept — and not a penny more. This is true for many industries, but especially in tech, where salary data is scant due to ever-changing programming languages, skills, and platforms.

Asking Perpetuates Past Unfairness

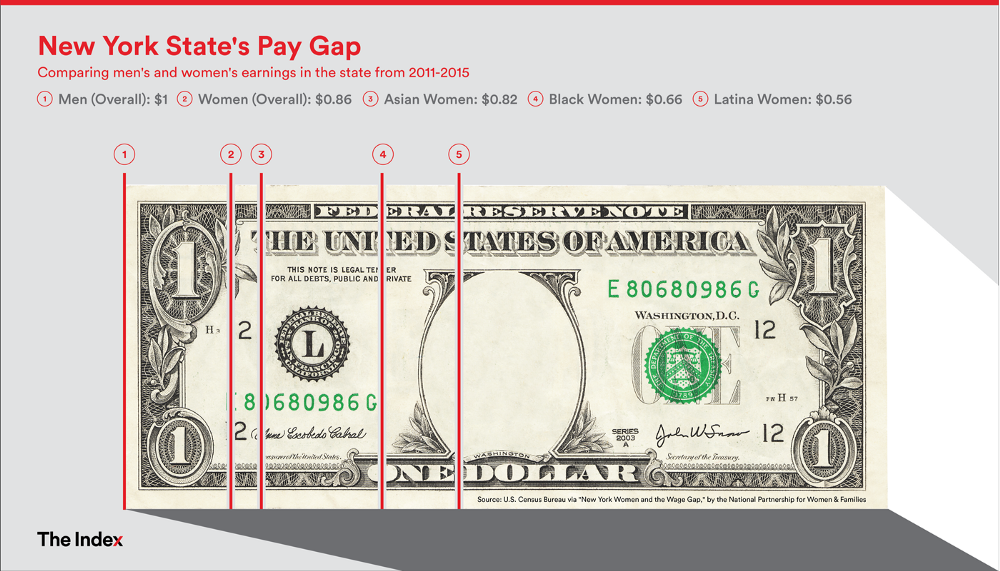

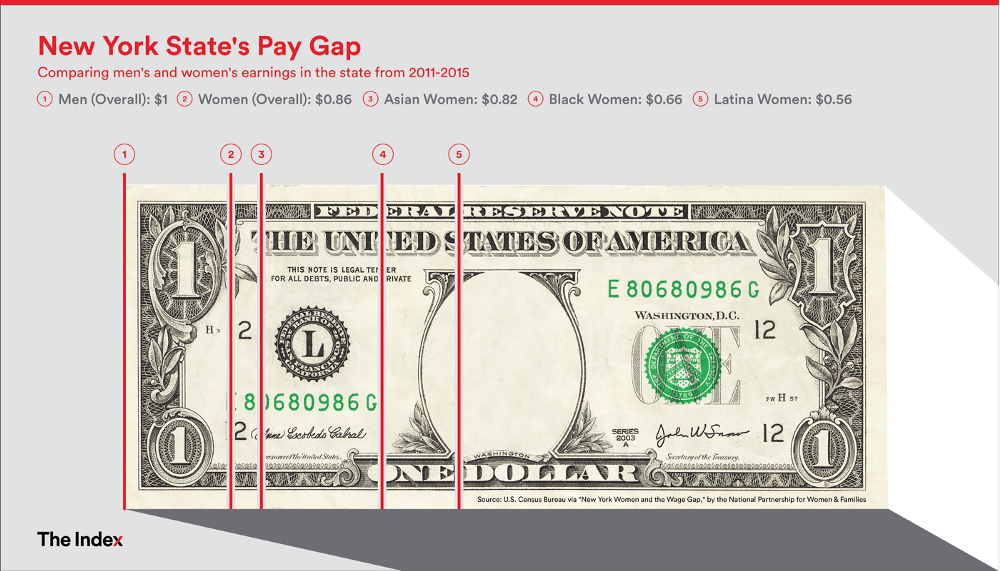

Asking candidates for their salary history is a key factor in perpetuating salary discrimination and the wage gap. The wage gap in New York State, where the global tech education company General Assembly is headquartered, specifically impacts women the most. New York women with full-time, year-round jobs were paid $0.86 cents for every dollar paid to men between 2011–2015, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. And the pay gap impacts black, Latina, and Asian women even further: During that time, among New York women who hold full-time, year-round jobs, black women were paid 66 cents, Latinas were paid 56 cents, and Asian women were paid 82 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men, according to the U.S. Census Bureau via “New York Women and the Wage Gap,” a resource from the National Partnership for Women & Families.

Lawmakers Are Fighting the Practice

Across the U.S., cities like Philadelphia and entire states including Massachusetts, Delaware, and Oregon, are already taking action to close these persistent gaps. Today we’re proud to show our support for a groundbreaking bill in New York, A.6707/S.5233, that, if passed, would ban employers from asking for candidate and employee salary history. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio already took steps locally to sign a bill last month that prohibits employers in the city from asking for job applicants’ salary history. This new legislation would apply to the entire state.

At General Assembly, we work with students from education through employment: We train them in coding, data science, and UX design, then coach graduates through their job search. Because of our commitment to cultivating hiring pipelines across our global community, we interact constantly with hiring managers and candidates, and know firsthand that not asking for salary history can have a positive impact from both the company and employee perspective. Employees are pleased with the transparency and feel they are paid fairly — which contributes to higher engagement with their work from Day One.

In 2016, after Massachusetts became the first state to pass a pay equity law banning employers from asking job candidates for salary history, we began training our talent acquisition team to ask about salary expectations, not salary history. So far we’ve seen amazing results, including consistent salaries by job level, employees feeling engaged and valued, and students equipped with the training and knowledge to pursue fair compensation.

For example, we hire from various industries including education, technology, and management consulting to fill roles at all levels across our headquarters and global campuses. This is a challenge, as candidate salary expectations vary greatly — and without careful planning it can result in wide pay disparities. In our hiring processes, we’ve seen salary expectation discrepancies as high as $150K between candidates. These sums are usually determined by a candidate’s current salary — and the numbers often correlate with the gender and race wage gaps that permeate our society.

Once We Made the Change, We Saw Improvements

Once we stopped asking candidates for salary data and instead offered a salary range for each position, we found that it not only simplified the conversation about salary, but also helped to ensure that new hires for a role are paid equally and fairly. This leads to fewer conversations about fair pay later on, and employees feel that they are valued by their managers and the company.

Not asking for salary data requires companies to be more proactive and thoughtful in planning for employee compensation. Leaders must now leverage salary data, think through compensation philosophy and job levels, and make thoughtful decisions about their talent and people investments. Factors to consider include, but are not limited to, the candidate’s specialized skills, the impact the role has on the business, and the effort required to ensure others with similar responsibilities across departments receive equal pay.

Compensation analysis is complex and should be informed by proper salary data from sources like the compensation data company PayScale and technology insights platform Radford, as well as internal leveling processes. Basing employee compensation on pay ranges driven by a purposeful compensation philosophy instead of salary history is a challenging behavior shift for many companies, but making this extra effort is good business. It’s the way compensation should work, and the future of successful, people-centric organizations.

But good business is just one element of this issue. Most importantly, this is about fairness and equity. Marginalized groups impacted by pay disparity make significantly less money over time, meaning that women and people of color may struggle to support themselves throughout their lives. When salaries are based on compensation history instead of required skills and the value the role brings to the business, leaders perpetuate a vicious cycle — and companies have to take the initiative to correct it.

A Ban on the Past Salary Question Will Result in a More Diverse and Fair Tech Industry

At GA, we have a unique perspective in that pay inequity is an issue for both our HR department and our students. Many of our students train with us to entirely change their careers to become software engineers, data scientists, and UX designers. Those in our full-time programs work closely with career coaches, who help students navigate salary expectations and negotiations based on their experience, local markets, and other factors. After investing so much time and effort into this difficult transition, there is nothing worse than the thought of our students not being paid a fair salary to reflect their new skills.

We also strive to increase equity across the tech industry beyond the HR department, and have several programs that benefit individuals most likely to be affected by the wage gap. CodeBridge, developed and implemented in partnership with our friends at the job-training nonprofit Per Scholas, focuses specifically on empowering top-tier underserved and overlooked talent with digital skills and helping them get jobs. The average pre-training household income for Per Scholas students is $7,000 per year, and most have not had the same educational and professional opportunities as many who come to General Assembly. In another program, we’ve partnered with the New York City Tech Talent Pipeline to train low-income New Yorkers to become data analysts and web developers.

The talent coming out of these programs is extraordinary, with skills on par with their peers who have four-year degrees and higher incomes. There’s no reason why highly skilled tech talent should be paid less simply because they were born into a family with less access to education and opportunity, or had faced similar barriers themselves.

We’re proud to support New York’s salary history ban for these reasons, and encourage everyone reading — regardless of the outcome of this bill — to eliminate salary history from global compensation decisions and help close the wage gap.

This piece was originally posted in The Index by Catie Brand, Director of Talent Acquisition at General Assembly.

About the Author

Catie Brand is the director of talent acquisition at General Assembly. With a dual degree in English and business administration from Boston University, Catie has worked for the executive search firm Daversa, where she placed VP- and C-level candidates at technology companies including eBay and Gilt. She is a co-founder of Krow, a talent branding and mobile optimization tool for recruiters, and joined GA in 2014.

About General Assembly

Boost your career or transform your business through innovative events, workshops, and courses in web development, user experience design, data science, and more. Employers seeking an edge in today’s digital economy can assess job candidates and current teams through GA’s Credentials division or grow employee skills through our corporate training programs.