The gender pay gap is an issue that lies close to my heart. I am a woman who took science and maths at school, studied an Economics degree, and now works in finance; all male-dominated fields. I don’t think I should earn less than my colleagues because I’m a woman — and there’s no evidence to suggest that I’m less productive because of it.

Granted, the gap has reduced over time. But data released by 10,000 large UK companies in 2018 showed that it still exists in favour of men for all sectors. There’s clearly still a long way to go.

The gender pay gap: Defined

Before we continue, I think it’s useful to properly define “gender pay gap”. What we mean is:

The difference between men’s and women’s — usually average — earnings, as a proportion of men’s earnings.

This gap is often confused with discrimination. But discrimination does unfortunately still occur. A colleague told me about a previous job application, where during the interview, her potential employer had asked whether she had a boyfriend and if she planned on having children in the near future. This was a case of blatant discrimination. He didn’t want to hire her due to the “risk” of her having children — something that wouldn’t have been an issue had she been a man.

Even though in the UK this shouldn’t happen, it clearly still does on occasion. This is a real and worrying issue, but the gender pay gap is more than this.

What else is to blame?

An Institute for Fiscal Studies paper finds that the most significant factor in explaining the gender pay gap in the UK is childbirth. This is because of its resultant effects on women’s accumulation of labour market experience.

On entry to the labour market, there is virtually no difference in men’s and women’s wages. This grows significantly from the ages of the late-20s.

Over the two-year period ranging one year either side of the birth of a woman’s first child, women’s employment rate drops significantly. For women with GCSEs, it drops by 30 percentage points.

As well as the employment gap that develops following childbirth, a gap also opens up between men’s and women’s rates of full-time work — many women move to working part-time. Evidence suggests that, in terms of the accumulation of experience, there are very little returns to part-time work.

It’s hardly surprising, then, that the gender wage gap widens so significantly, coinciding with the average age of first-time mothers being 28.8 years.

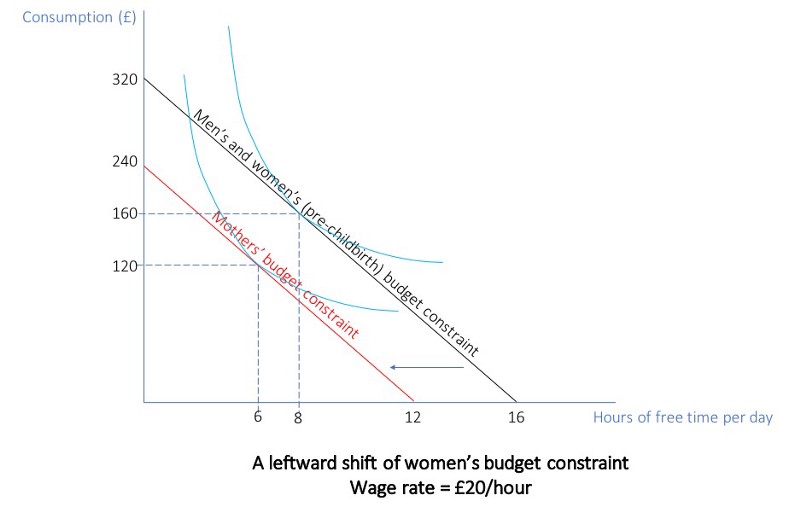

The following models the effect of having children on women’s choice of labour hours outside the home. The curved lines are indifference curves. Each point on a curve gives the same utility — an individual is “indifferent” between any point on the curve.

The model assumes that individuals need 8 hours a day for biological maintenance (eating, sleeping, etc.), caring for a child takes 4 hours a day, and women are totally responsible for this. We can see how the hours required in caring for a child reduces mothers’ available working hours, resulting in fewer hours of outside employment — and lower earnings.

That women complete all childcare is not strictly true — this is just an assumption to help illustrate a point — but women are responsible for nearly three-quarters of total childcare time.

Occupation is another factor that is found to contribute to the gender pay gap. An Office for National Statistics paper finds that differences in the occupations held by men and women can account for 23.0% of their differences in earnings.

Men are more likely to hold lower-skilled, and therefore lower-paid, positions. But — crucially — men are far more likely to hold the most senior, and most highly-paid, positions, such as chief executive and managerial roles.

Now we know why, what can we do?

The underlying issue is that women remain primary caregivers. We need to lessen the burden on women as they become mothers to make it easier for them to stay in employment.

One way to help would be to encourage men to take on more child-caring responsibilities.

The Shared Parental Leave policy is already in place, whereby both mothers and fathers are entitled to take time off following childbirth. But fathers should be more strongly encouraged to make use of this. Senior staff should lead by example and employers should make sure that all employees, men and women alike, know that they could be entitled to this.

Some employers also already offer flexible working, such as changes in “traditional” hours, flexi-time and the option to work from home. This can afford employees the opportunity to more easily combine work and outside (e.g. caring) responsibilities. Employers that don’t yet offer this should follow suit, but again, flexible working should be highlighted as a benefit for all — not just for women.

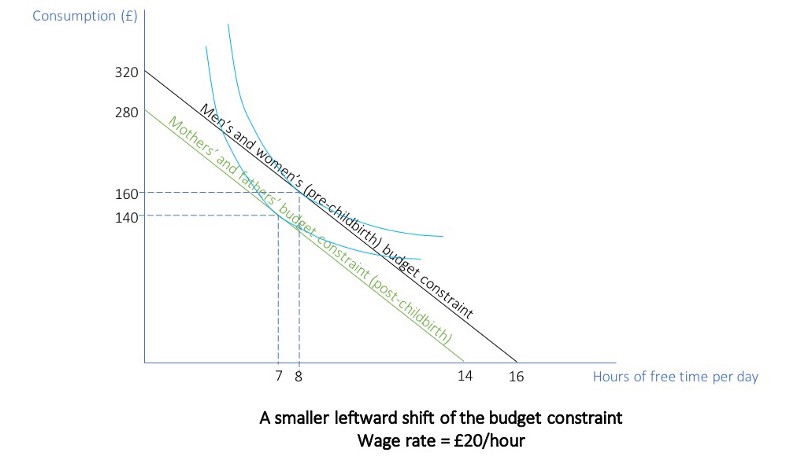

The greater use of these policies could lead to more equal childcare responsibilities between parents, and should make it easier for them to manage work around their childcare responsibilities. Returning to our model, we can see how this should have a beneficial effect on mothers’ ability to continue working.

Through affording women greater flexibility at work, and encouraging fathers to take on more responsibility in caring for their children, the hours women are able to commit to outside employment are not so reduced. More mothers should be able to remain in employment and full-time work.

What about the occupation issue? We need more visibility of women at the senior level. As of July last year, at FTSE 250 firms, there were only 30 women in full-time executive roles. This article paints an even more shocking picture. Increased flexibility should also help with making these kinds of roles more accessible to women with commitments outside work.

Looking at recruitment practices, shortlists for promotion or recruitment should include more than one woman. If there’s only one, there’s statistically no chance she’ll be offered the job. Evidence like this should be used in designing practices such that we see greater representation of women at the top.

“Work Like a Woman”

Mary Portas’ book is proving interesting, if in some parts troubling, reading. I don’t agree with everything she says, but something I can get behind is this:

We need to reshape attitudes of what it means to be a leader.

Historically, this was horrendously long hours, you are your job and your job is you. For many people — women and men alike — if this is what it takes to lead, it’s just not an option. And I certainly wouldn’t choose it if that’s what it took.

People can be great leaders and still have a life. Mothers, fathers and anyone with responsibilities outside of work can achieve their potential to be so with the right support and the right working environment.

If we change how we think about, and what we expect of, senior staff, we can change working culture to reflect modern life and attitudes. Holding a senior position doesn’t mean having to sacrifice (every/some)thing else. If we can make this a reality, more mothers, fathers — and anyone who values more than just their job — will be the successful leaders they’re capable of being.

In the process we might just see parity in men’s and women’s earnings.

This piece was originally published on Medium, and republished here with permission, and republished here with permission.